info@alexramsay.ca | 1-905-510-0396

info@alexramsay.ca | 1-905-510-0396

Specialties >> Return to Articles List

Resettlement Action Plans

For major international development projects, where the locally affected population is required to be relocated out of the project development footprint and zone of influence, a Resttlement Action Plan may be required. Experience gained in Kazakhstan (RoK) and elsewhere from major oil and gas and mining projects is instructive on how this may be achieved so that the Project Affected Community is able to transition successfully, in a sustainable way. This involves consulting with the PACs and local authorities to assure that the options being pursued, typically involving replacing agricultural, fishery or forestry based endeavours with similar income earning activities in a new, adjacent area. This is no easy task since hitherto adjacent unused land or water resources, by definition, may already be subject to use by well established PACs, or if not, may be unproductive, thus requiring major inputs such as irrigation. So integrating a PAC into a new rural area, or alternatively urban areas, requires adequate funding to assure that lands or fishing rights can be acquired, or training provided to transition into an urban context. A combination of these may also be required in keeping with the universal trend towards urbanization, with the effect being more sparsely populated, mechanized rural work environments which rely on high capital inputs for resource extraction or agricultural, forestry or fishing.

Involuntary resettlement, as defined by IFC in Performance Standard 5, refers to both "physical displacement (relocation or loss of shelter) and to economic displacement (loss of assets or access to assets that leads to loss of income sources or other means of livelihood) as a result of project-related land acquisition and/or restrictions on land use. Resettlement is considered involuntary when affected persons or communities do not have the right to refuse land acquisition or restrictions on land use that result in physical or economic displacement. This occurs in cases of (i) lawful expropriation or temporary or permanent restrictions on land use and (ii) negotiated settlements in which the buyer can resort to expropriation or impose legal restrictions on land use if negotiations with the seller fail. "

The World Bank in its Operational Manual, at OP 4.12, indicates that from its experience:' Involuntary resettlement may cause severe long-term hardship, impoverishment and environmental damage unless appropriate measures are carefully planned and carried out." Thus, avoidance is the first option and for many linear development projects such as pipelines and hydro lines this is feasible, since routing around PACs or individual residences is readily achieved. However, for many industrial projects including refineries, mining, hydro-electric and airports, with large footprints, i.e. a Total Exclusion Zone {in the Former Soviet Union, the Sanitary Protection Zone (SPZ)} may require the relocation of PACs, a safe distance away. As an example, in Western Kazakhstan, for the Kashagan onshore oil processing facility, a 7 km Sanitary Protection Zone was established, by law, due to possible health and safety impacts, including those associated with the handling of toxic hydrogen sulfide. Elsewhere for major facilities this may relate to health and safety issues including noise and explosion and/or potential for fire. Another resettlement plan is progressing in Western Kazakhstan with the effective expansion of the 5 km SPZ for the Karachaganak oil and gas condensate field, to include Berezovka, a town of 1581 people who have after more than a decade of negotations with the competent authorities and KPO achieved their goal of resettlement, in keeping with the previous resettlement of the village of Tungush in 2003. Tungush was inside the 5 km SPZ and was succesfully resettled to an apartment block in Uralsk. The expanded SPZ and further relocation, due in part to apparent hydrogen sulfide poisoning incidents in 2014 and 2015, with school childeren fainting, illustrates the need to carefully carry out a Social and Health Impacts Assessment initially, and also on an ongoing basis for expansion phases, so that local residents are relocated in a timely manner, a safe distance away, due to predicted, rather than observed health and safety risks. Whereas the Tungush resettlement cost in the order of $10 million USD, a more extensive resettlement in Western Kazakhstan for Sarykamys and Keneral Farms involving relocation of some 3500 residents from a 10 km SPZ has been reported to have cost TCO $100 million USD.

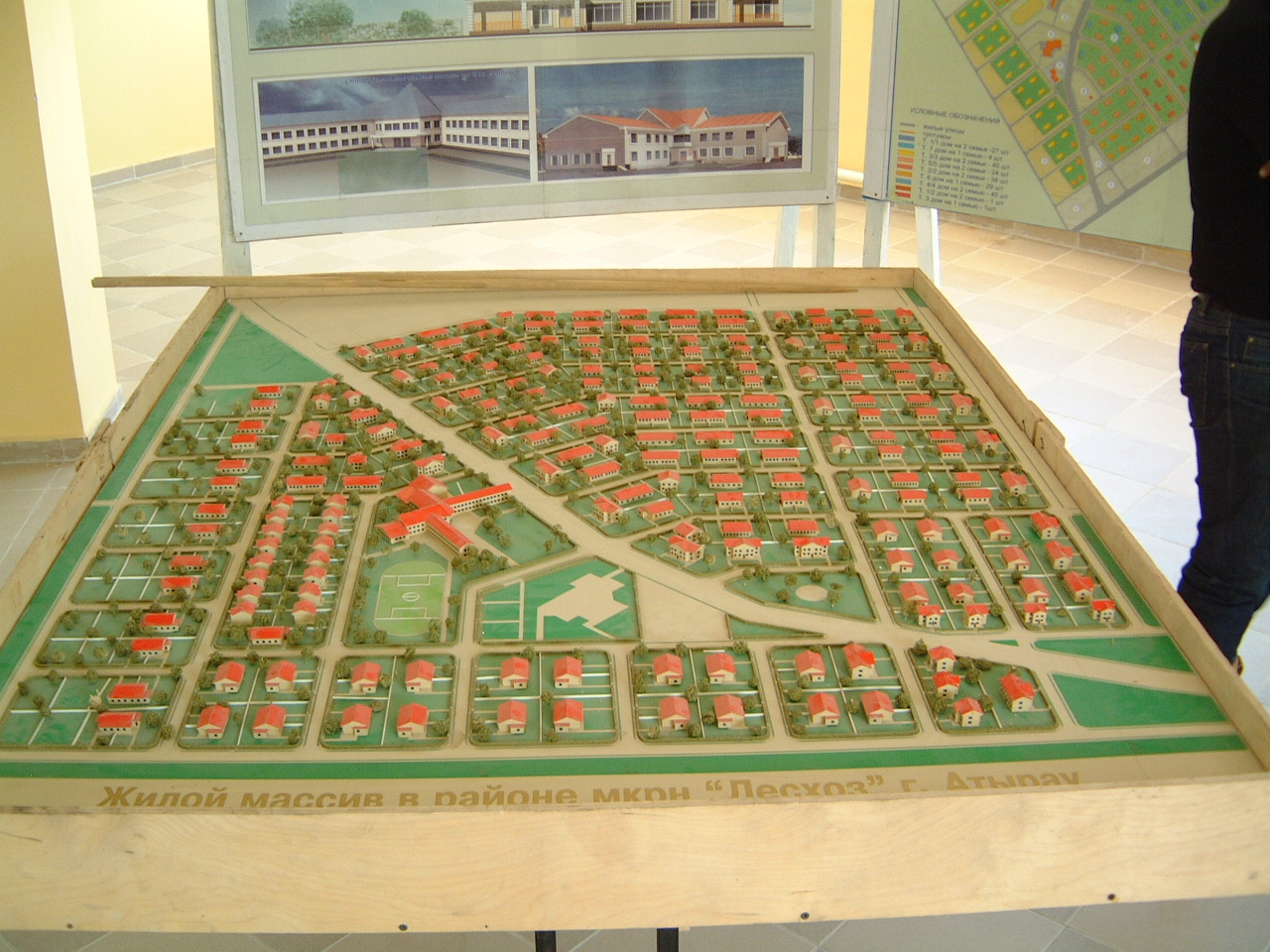

Cooperation of local authorities and companies in consulting with PACs is needed so that the residential options fit with the residents' needs. For the ongoing Berezkova resettlement, two options are available - apartment or cottages in Aksai. This is similar to the Sarykamys RAP which provided for suburban housing in Atyrau (see photos below), or alternatively, a rural house with a livestock shed in New Karaton, on the open steppe, near Kulsary. As illustrated below, modern housing, with central heating and a cultural centre, like the community yurt llustrated, provided a significant improvement over the run down, delapidated housing left behind in Sarykamys (last photo). In RoK the RAP is implemented by the local government with funding and oversight provided by the project proponent.

-

Those displaced are to be informed about their options and rights regarding resettlement;

-

Consultation about technically and economically feasible alternatives and agreement as to the ultimate scenario;

-

Prompt compensation at full replacement cost for losses of assets attributable directly to the project.

To help eliminate the need to use governmental authority to enforce relocation through expropriation of land, clients are encouraged by IFC to use negotiated settlements, meeting the requirements of Performance Standard 5, even if they have the legal means to acquire land without the seller’s consent. Hence the need for skilled consultation with PACs and negotiations that yield a positive win-win result for both the proponent and those to be relocated.

RAPs ( see IFC 2012) should be developed where physical and/or economic displacement resulting from the following types of land-related transactions applies where:

-

Land rights or land use rights acquired through expropriation in accordance with the legal system of the host country or where these rights are acquired through negotiated settlements with property owners or those with legal rights to the land, if failure to reach settlement would have resulted in expropriation;

-

Project situations where involuntary restrictions on land use and access to natural resources cause a community or groups within a community to lose access to resource usage where they have traditional or recognizable usage rights;

-

Certain project situations requiring evictions of people occupying land without formal, traditional, or recognizable usage rights;

-

Restrictions on access to land or use of other resources including communal property and natural resources such as marine and aquatic resources, timber and non-timber forest products, freshwater, medicinal plants, hunting and gathering grounds and grazing and cropping areas.

Specifics to be included in a RAP

-

Project Description detailing alternatives considered to minimize displacement and the Total Exclusion Zone, secondary restricted area due to noise and emergency response criteria;

-

Potential impacts such as air pollution, fire, explosion, noise and physical displacement by plant and infrastructure as set out in the project ESHIA and detailed design;

-

Objectives of the RAP e.g. relocation of displaced residents and other land/water resource users in accordane with local laws and IFC PS 5 so that livelihoods improve as a result;

-

Census, socio-economic and asset surveys to docment the scope of the resettlement plan;

-

Legal and institutional framework governing the project and RAP so that all stakeholders understand the rules of engagement;

-

Compensation framework and Livelihood Resoration Plan including eligibility and valuation methods as well as compensation principles for agriculture, fisheries and forestry i.e replacement value in cash, or in kind to assure sustainability over the long term;

-

Resettlement measures including site selection and preparation and relocation with timeline for provision of housing, infrastructure and social services;

-

Community consultation and participation with the identifcation of represtatives, committees and grievance mechanism;

-

Costs and budget and monotoring and evaluation to take place through the RAP process.

There has to be flexibility built into the plan to accomodate changes over time and lessons learnt. One obvious challenge is meeting the sustainability of agricultural communities where subsistence farming exists. In the case of Keneral Farms, a former Soviet collective, whereas the state garanteed adequate surrounding grazing lands, the New Karaton location cannot. One livestock shed per family would not permit agricultural sustainability, so alternatives, including grazing cattle a distance from the new village, is an option. With increased grazing pressure on poor land improved range management practices need to be explored with appropriate sudsidies, to assure the success of the transition to animal husbandry within a reasonable distance of the resettlement area. Similarly for those moving to the city who have have traditionally subsisted on animal husbandry. Job training, either project related, or related to supplying local services, needs to be provided preferentially to those relocated. In this regard ongoing evaluation and monitoring is required and support provided to assure the success of the resettlement action plan.

Contact info@alexramsay.ca for enquiries about resettlement action plans.